Genre: Turn-based strategy

Year: 1996

Developed by: MicroProse

Published by: MicroProse

Platforms: PC, Mac, Playstation

#204

Feeling Like: Fanatical

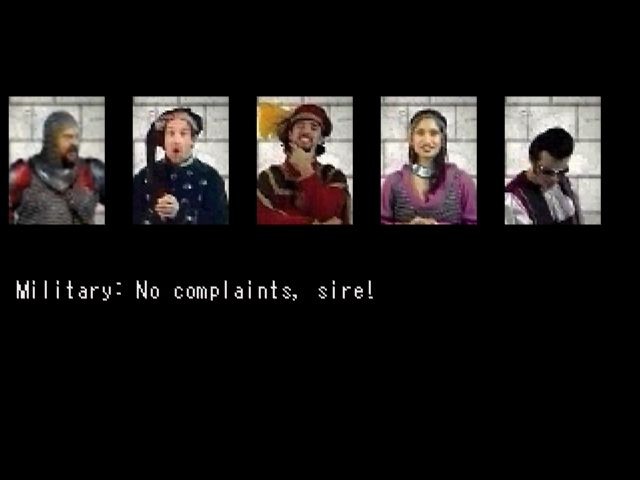

I’ve already covered a few Civilization games, so there isn’t much new I can say here. It’s difficult to say precisely why the sequel was better than the original but I will say five years, particularly from 1991 to 1996, saw an enormous leap in graphical fidelity and PC hardware. Take a look at the screenshots side by side and you can easily see why Civilization 2 really benefited from this jump in technology.

You could hardly have full motion video of actors portraying your council yelling at you to increase your military spend on a 1991 PC, after all.

When it comes to roadblocks like these, I tend to outsource to my smarter, cooler friends. And there’s nobody I associate Civilization 2 with more than my buddy Kasim.

(Kasim)

I haven’t been a serious gamer since my early twenties, and the slow taper of my relationship with this pastime feels unaccountable yet inevitable. Adulting is part of it, but I’m not sure it’s all of it? Maybe I can explain, all through a game I played to death that came out back in 1996: Sid Meier’s Civilization II.

My earliest memory of the franchise is watching my friend Dorian play Civ I. I always picture the alien DOS commands he used to open it before I even picture the game; my friend seemed somehow more serious than me, who was familiar only with the logical operating system of my dad’s Macintosh LC; why would you need to know how things worked under the hood? He had to learn a whole language to begin to play a game, not just open a game file that had been installed off a sheeny desktop. But what a game it was, once you got there.

I remember the incongruity of the cities with numbers standing for population, standing out vibrantly against the matte green and blue of land and water. The brutality of the game in its early form. New technologies learned simply as a means to a violent end of imperialist victory. No other way to success seemed possible. I never saw enough of it to see it played through; the Civ I maps I can remember now all had darkness around the edges, still undiscovered possibilities beyond reach.

Civilization II was the first game in the franchise I got to play at home, when it was ported to Mac. I must have been 12, and I was instantly hooked. The new isometric perspective alone somehow made the world-building possibilities feel that much more expansive. Or maybe that was a reflection of what was happening in my own mind – it spoke to a habit of mine, developed a few years before, of reading the atlas, obsessing over human geography, even in the middle of class while I was supposed to be learning yet more about the fur trade. Capitals, populations, forms of government. My cousins remember me best for spending one beach holiday inside, endlessly copying out maps freehand from that atlas. I never developed that good an eye for scale, or a strong line, but the project spoke to my desire to map the world, even though I never finished all 191 (at the time) countries in the world.

Turn-based strategy in this form already satisfied that completist instinct in me, but now Civ II offered that much more to complete. Suddenly there were civs galore – indulge your inner history nerd by playing as the Persian, Japanese, even Carthaginian empires; even choose your ruler’s gender. It felt like there was an advanced version of everything; barbarian horsemen became legions and eventually partisans, settlers turned into engineers and could transform the landscape. The technology tree that gave you these new units necessarily also had been expanded, and gave you access to new wonders of the world and other city improvements.

Of course, with these bigger possibilities came new challenges. Here was a game that took climate change seriously – engineer your cities’ resources too much and an overpopulated world could trigger climate change, marring the landscape with pollution (the same being true of nuclear war). This was just a taste of the anarchic quality to Civ II, as clearly the developers had been given a little free rein: selecting the “bloodlust” endgame switched off the space race victory to ensure a Risk-style victory by world domination. If you ever sweated a loss in a game you were really satisfied with, you could always toggle cheats on in the full menu helpfully dedicated to this purpose!

Then there were the Ancient Rome and WWII simulations in which it was always weirdly tempting to play as the Ptolemaic Greeks in Egypt or fascist Spain and ward off the big threats of expansionist Rome and Germany, respectively, and make whatever small gains of your own that you could. I still remember my proud take-over of Vichy France on behalf of Franco in one WWII play-through. The what-ifs are tantalizing: what would the world look like if Rome never fell, but maybe never overextended and actually led the space race? Of course, it was always hard not to think now about the obvious choice of playing Axis, playing out a grim alternate history of the twentieth-century, Man in the High Castle-style.

After early campaigns where I figured out how to secure an imperialist victory, though, my approach to the game quickly turned maximalist. I found it tiresome to raise the difficulty beyond Prince, as early conflict and too many rivals building those key wonders of the Pyramids (granaries in all cities, which never becomes obsolete, meaning your cities take half as long to grow for the whole game) and the Great Wall (counts as city walls in all cities to up your defences’ effectiveness). I wanted my cities to become megalopolises, and became obsessed with optimal city placement, planting them so that no resource tiles would overlap in their territories. Actual victory over other civilizations became secondary; the process of growth felt more important to me.

Here’s where the game’s limitations under the hood, so to speak, became obvious. Grow your Civ big enough, and turns started to take forever, as even when you automated units you’d still need to watch each of them torturously progress across an increasingly gargantuan map before your turn was finally up. However, this level of involvement trained you to be a perfectionist. The automation at this point was unsophisticated enough that if you set triremes to go to an ocean tile far away, they’d often end their turn too far from land and get lost at sea. Drawing things out even further, the map had to refresh and centre each unit selected before you could give it orders, and for late games of a certain scale (or limitations on your CPU) lag became noticeable. If this level of detail makes it sound like I’ve recently played it through on an emulator, you’re right!

The third instalment in the franchise similarly rewarded this style of maximalist gameplay with fewer of the above annoyances, updating graphics somewhat and adding even more features – units, tech, improvements, tiles, etc. As a result Civ III was a game of choice during my undergrad days, and I would actually say I preferred it slightly to Civ II. It was when I got to Civilization IV that I lost interest in the franchise; so many new features and a reliance on much better automation meant that my micromanagerial style clashed with the necessity to develop a strategy that delegated production decisions more. I bought the game, but felt totally overwhelmed and barely ever played it.

Learning to delegate over being hyper-involved. The way Civilization changed I think also reflects my own coming of age. Going back to the game now, I realize how its conceit still has the potential to pull me into another world. But another thought occurs too as I think about what it means to be an adult – as much as I still enjoy the delicious irony of playing a game where Gandhi’s Indians can be the most war-like civilization, in these days where it feels like you can no longer reasonably assume everyone agrees that the Nazis were the bad guys in WWII, I wonder if my taste for a choose-your-own-adventure relationship with history has also changed. Which brings me back to the question I started with – what happened to my gamer self? I realize now it’s not so much a question of “did I change, or did the games change.” Now to be clear, I’m not saying, on this blog of all blogs, that growing up has to mean growing away from games. But in thinking about my own relationship with games through the lens of Civ II, I also think of how it inspired me to learn about world geography, history, and cultures. How, like all good teachers, you eventually move on, and form your own relationships with the ideas and skills you learn from them. For the interests the game sparked in me, then, it will always have a special place in my heart.

(Kasim’s writeup finished)

What else can I possibly say, other than if I was an eccentric billionaire, I’d commission Kasim to write the next 203 entries on the 500. Thanks buddy!